The Myth and the Reality of Modern Gold Mining in Alaska

As new gold projects rise in the Cook Inlet | Tikahtnu watershed, we have to ask: Is it really worth it? Gold still glitters in today’s economy — not just in jewelry or bank vaults, but in the circuitry of our phones and computers.

According to the World Gold Council, the average smartphone contains about 50 milligrams of gold — worth only a few dollars per device. But with nearly a billion phones produced each year, that’s billions of dollars’ worth of gold sitting in our pockets.

That global demand keeps the mining industry humming — and Alaska is in its sights. Gold helped shape Alaska’s early history, from the 19th-century rushes to Nome and Fairbanks to the industrial mines that dot the state today.

Now, with oil revenues falling, mining companies are touting new gold projects as an economic lifeline.

But the numbers tell a different story. Between 2009 and 2018, metal mining made up only about one-sixtieth of the revenue oil brought to Alaska’s economy. Even if mining doubled or tripled, it would barely make a dent in that gap. Most of the profits flow out of state — and most of the jobs do too.

A Better Path: Recycling What We Already Have

If gold’s economic benefits are small and its environmental risks are huge, the question becomes simple: Do we even need new gold mines?

The answer is no.

Globally, about a quarter of all gold demand is already met through recycling — recovering gold from old electronics, jewelry, and industrial waste.

The environmental benefits are staggering: producing gold from recycled sources emits 99.7% less greenhouse gas and uses 99.7% less water than mining the same amount from the ground.

In other words, the gold we need is already above ground.

Recycling, Not Mining: A Local Solution

Here in Cook Inlet, we’re doing our part.

Every year, Cook Inletkeeper hosts Electronics Recycling Events across the region — giving Alaskans a safe, responsible way to recycle their old phones, computers, and appliances.

These events don’t just keep toxic waste out of landfills; they recover valuable metals like gold, copper, cobalt, and lithium — materials worth far more in the circular economy than the same stuff buried beneath untouched land.

If these metals are worth mining, they’re worth recycling.

The Cost of Gold

The real cost of gold mining isn’t measured in dollars — it’s measured in damaged rivers, poisoned water, and lost salmon runs.

Gold is often found in rock laced with sulfide minerals. When those rocks are dug up and exposed to air and water, they react to form sulfuric acid — the same chemical found in car batteries. This acid seeps into nearby streams, lowering the pH and leaching heavy metals like arsenic, mercury, and zinc into the water. The result is acid mine drainage — a toxic brew that can devastate fish and aquatic life for centuries after a mine closes.

Johnson Tract Mine

The proposed Johnson Tract Gold Mine would sit within the boundaries of Lake Clark National Park, an area that has supported local communities, subsistence harvest, and ecotourism for generations.

Despite that, CIRI has leased the land to Contango Ore, which is fast-tracking the mine’s development. While the company describes it as a “short-term” 5–7-year project, the planned infrastructure tells a different story:

- 20 miles of new industrial road

- A shipping port in Tuxedni Bay

- A full-scale extraction operation within park boundaries

Once roads and ports are built, they rarely go away — and neither do their impacts on wildlife and clean water.

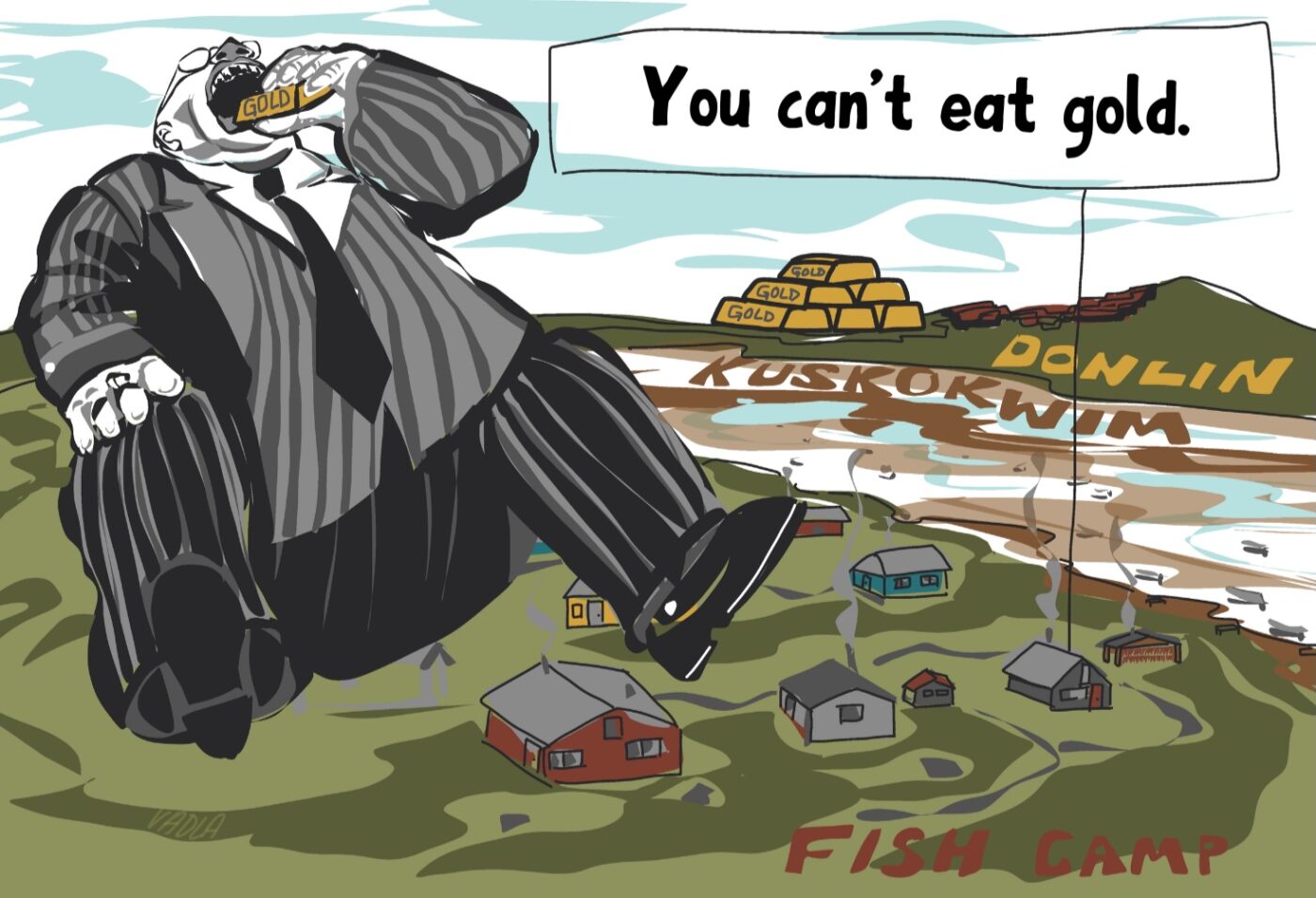

Donlin Gold Mine

Farther west, near the Kuskokwim River, the proposed Donlin Gold Mine would be one of the largest open-pit gold mines in the world.

Over its 27-year lifespan, Donlin is expected to generate 2.5 billion tons of waste rock — enough to fill 175,000 Olympic swimming pools — all held back by a tailings dam nearly 500 feet high and more than a mile long.

A breach could release catastrophic amounts of toxic waste into the Kuskokwim River system, threatening salmon habitat across vast swaths of southwest Alaska.

Even the project’s own environmental review acknowledged that the odds of a dam failure are about 1 in 50 over 20 years. Those might sound like decent odds — until you realize your odds of being in a fatal commercial plane crash are 1 in 11 million.

Communities along the Kuskokwim — Indigenous and rural, subsistence-based and salmon-dependent — should never have to live with those odds hanging over their rivers. If there were a 1 in 50 chance your plane would crash, would you still get on board?

The Real Treasure

Gold has always symbolized wealth. But in Alaska, real wealth still flows in our rivers, swims in our salmon runs, and fills the land we live on.

The projects we support at Inletkeeper — from electronics recycling to community-led climate solutions — help keep that wealth alive.

By keeping gold in the ground, we make room for something far more precious: Healthy waterways. Strong salmon runs. Thriving communities. Clean water for generations to come.