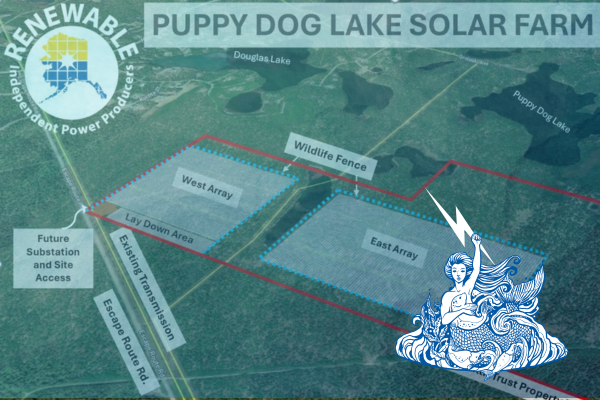

A year ago, the developers of the planned Puppy Dog lake solar farm in Nikiski signed a contract to sell solar power to Homer Electric Association (HEA) for less than the current cost of HEA’s gas-generated power. The solar project was planned to meet about 12% of HEA’s annual electrical needs, and would save Homer residents incrementally more and more money as natural gas costs inevitably rise. It was a deal too good to refuse — HEA’s board unanimously approved the contract in August 2024. Puppy Dog Lake was set to become not only Alaska’s biggest solar facility at 45 megawatts, but also HEA’s first significant new non-gas power source since the state-built Bradley Lake hydroelectric plant was completed in 1991.

But less than a year later, HEA has walked away from the long-term cost reductions of solar power, and instead focused on pushing for expensive gas and higher long-term prices for its members. The result? An annual gut punch to everyone’s wallet.

How did we get here?

Bringing energy investment to Alaska is challenging due to the difficulty of earning attractive returns in a high-cost state with a small population of potential customers. Our local gas market encountered this reality in the 2010s, when the state spent at least $1.6 billion in tax credit subsidies to prop up investment in Cook Inlet gas after major drillers moved their dollars elsewhere. Cheaper energy for Alaskans does not necessarily mean attractive returns for investors who can spend their capital anywhere. This is also true of competitive technologies like solar. Puppy Dog Lake was the work of a small Alaska startup called Renewable Independent Producer (RIPP), which financed its projects through a partnership with New York-based CleanCapital. This resulted in the 8.5 megawatt Houston Solar Farm, which is contracted to sell power to Matanusk Electric Association for the next 25 years at an even lower rate than Puppy Dog Lake. RIPP was set to bring the fruit of this partnership to HEA — until the financing equation threatened to change.

Although the Investment Tax Credits that could reimburse 40% of the cost of Puppy Dog Lake weren’t repealed until the passage of the “Big Beautiful Bill” in early July, the prospect that they might be repealed was concerning enough for CleanCapital to hedge its commitment in February. Without their funding, RIPP was unable to meet its contract price and withdrew the deal with HEA. Adding 40% to project costs would eat a big piece of CleanCapital’s return, but even a more expensive Puppy Dog Lake solar farm would create significant savings against the rising expense of Cook Inlet gas and imported LNG. HEA members would still benefit from the cost savings of solar power, even if it doesn’t make sense for CleanCapital’s goals.

RIPP held an auction for the Puppy Dog Lake plans, and in April 2025, the HEA board unanimously gave the co-op permission to bid. To develop the project, HEA planned to re-purpose a loan from the federal “Powering Affordable Clean Energy” (PACE) program. HEA was originally given a $100 million PACE loan, 50-60% forgivable, to double the capacity of its battery storage system in Soldotna.

By early June, however, I had heard that the auction for Puppy Dog Lake had come and gone — without HEA ever making a bid. HEA General manager Brad Janorschke later confirmed this, saying there had been concerns about the land agreement (the solar farm would have been on state land leased from the Mental Health Trust) but declining to give details. A more important reason, Janorschke said, was the hope that another private developer would win the project and offer HEA a power sales contract without the co-op needing to risk any of its own capital. Janorschke said in July that he didn’t know whether there had been other bids.

It’s possible that a new developer could take on the risk to sell us the power. But another outcome, made more likely by the shrinking returns on renewable investment and a hostile federal government, is that the project won’t find a developer. The consequence? HEA members will lose the opportunity for cheaper power and stay shackled to rising gas prices.

The “Big Beautiful Bill” that Congress passed in early July does what CleanCapital feared: it ends the tax credits for wind and solar. However, projects that start construction by July 2026 will still be eligible for the 40% cost reduction. Though HEA flirted with the possibility of other solar projects, Janorschke has decided to pass on this final opportunity and won’t be trying to get a wind or solar project underway before the deadline.

After declining Puppy Dog Lake, HEA investigated the alternative of installing solar arrays around its substations. Presenting to the board in June, HEA’s Mike Salzetti said an engineering consultant had evaluated land near existing substations as sites for a Puppy Dog Lake-sized solar array to be built with the once-again-redirected PACE loan. Two months later, Janorschke said HEA is dropping those plans as well due to expected resistance from the federal government. In the August HEA meeting, he told the board that, because others in the utility industry had told him that the federal government won’t grant Environmental Impact Statements to wind and solar projects, the $100 million PACE loan would now be spent on HEA’s 5 MW Grant Lake hydroelectric project.

With gas prices continuing their much-predicted climb, solar power still makes too much sense to be delayed for long. But with the window for subsidized investment closing, we will pay more for it when it comes – and in the meantime, we’ll pay more for gas we could have otherwise conserved. In March, I wrote “The High Cost of HEA’s Lost Time,” an article about how HEA’s failure to diversify is making energy more expensive and vulnerable, especially after the co-op ended its renewable goal — HEA’s only public-facing, measurable, and time-bound commitment to changing where our power comes from. But now the cancellation of tax credits has made the cost of lost time far higher. After more than a decade of warnings of rising prices and increased uncertainty for Cook Inlet gas, the only conservation strategy that HEA has adopted is to cross its fingers and hope for luck. The investment incentives available for two and a half years under the Inflation Reduction Act were the best stroke of luck it could have hoped for. But subsidies help those who help themselves.