Electric cooperatives are run by leaders elected by their member-owners – that is, everyone who pays an electric bill. These boards are meant to vote on the direction of the co-op and to approve its major decisions. But when it comes to the highly consequential conversations that co-op managers have with legislators in Juneau, the boards and the members they represent aren’t in the loop.

For example: on May 2, the managers of the four Railbelt co-ops (plus Seward’s city-owned utility) signed a letter to the co-chairs of the House Finance Committee calling for completion of federal permitting for the proposed Susitna River dam, a state-led megaproject that’s been dormant since funding cuts in 2014.

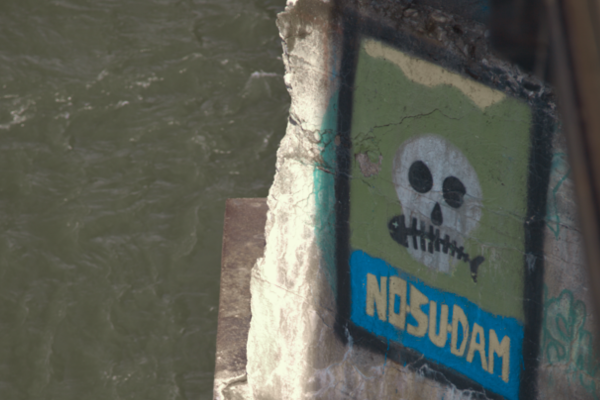

Inletkeeper has opposed the Su Dam because of its potential to damage the hydrology of the Susitna River, a vital artery of Cook Inlet’s watershed. As Inletkeeper’s March 2012 resolution against the dam stated, “the scale and purpose of the dam will invariably impact water flow regimes, ice patterns, fish habitat, and temperatures that will adversely affect salmon.”

Who decided that the most urgent action for our energy future is asking our cash-strapped state to pour more money into a horrendously expensive dam project? The letter to the co-chairs of the House Finance Committee was, as noted, signed by all the utility managers. But none of the co-op boards, who were elected to steer large decisions in the interest of members, held a vote on whether or not to prioritize the Su dam or to push for re-starting the permitting process. Based on conversations with some board members, few of them seemed even aware of the letter.

The Alaska Energy Authority estimates it has completed about two-thirds of the Su Dam’s federal licensing process. In 2013, just before the project was put on ice, the Anchorage Daily News reported that Alaska Energy Authority sought $247.5 million over the next three years (about $341 million in 2025 dollars) to complete federally-required studies.

Although it’s unlikely that next year’s state budget will include funding, the letter has raised interest from Alaskan policymakers. Senator Jesse Bjorkman, representing the northern Kenai Peninsula, made an out-of-the-blue comment in support of the Su dam at a May 7 legislative committee meeting.

“There is immense potential with Susitna Watana,” Bjorkman said. “My utility as well as all of yours have talked for many years about completing the permitting process for that project as well as moving forward.”

This hearing, in the Senate Labor and Committee that Bjorkman chairs, was the first for Senate Bill 149, a Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPS) bill that would require the utilities to be 55% renewable by 2035. Last year, Bjorkman was grandstanding about his intent to kill a previous RPS bill in his committee, but the utility push for the Su Dam apparently motivated him to finally give the RPS bill a hearing.

Wind and solar skeptics paint themselves as champions of “common sense” energy, by which they usually mean “firm” power that doesn’t have the unpredictable variability of wind and sun. But when such “common sense” leads them to tout giant, expensive, slow-moving megaprojects like the Su Dam as solutions to the urgent problem of natural gas shortfalls, they deserve pushback. Wind and solar are mature technologies that have reduced energy costs in many diverse systems in many parts of the world, once utilities make the investments and operational changes needed to deal with variability. In March, the engineering consultants E3 found that the Railbelt could add enough wind power to meet 25% of its annual demand – and on occasion up to 70% of instantaneous demand – without raising reliability concerns. This would require some operational changes, but no investment in new transmission.

The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) previously modeled an economically optimal generation mix for the Railbelt and found it would consist of 76% renewable energy. Their model was based on large wind farms, firmed up by limited hydro power and the existing gas generation fleet (although operating far less and burning far less fuel), with a smidge of solar on top to grab the summer sun. NREL estimates this scenario would have a net cumulative savings – accounting for the cost of integrating variable generation – of $1.3 billion by 2040.

Reaching these benefits will require the four utilities that operate our energy system to change how they function, how they plan, and how they work together – a challenge, but an achievable and worthwhile one. Their managers, though, seem to be seeking an easier course – calling for millions in public money to be spent on a dubious and ecologically destructive dam. They made this decision without their boards and without the members they represent.